As we already did earlier, we once again asked you how afraid were you, how concerned and how much you spent thinking about coronavirus, did it seem to you that infection could be contained and how serious the infection was, what you did to protect yourselves and the others, but also what sources of information did you trust and where did the information you trust came from. Did anything change during the two months that passed from the time the state of emergency was lifted?

The state of emergency itself lasted for two months and our study Psychological Profile of the Pandemic in Serbia mapped three psychological stages.

From the initial shock and state of alertness, through adaptation to the new circumstances and finally to the unexpected and sudden relaxation after the longest curfew. These three psychological stages during the state of emergency differ among themselves in terms of negative emotions due to COVID-19, trust in different sources of information and preventive and protective behaviour. Suddenly, when we found out about the first case in March, we entered the first, acute stage, which lasted from 8 to 25 March during which concerns caused by the situation sharply increased, followed by increase in rated credibility of information coming from different sources, as well as in the frequency and commitment to preventive behaviour. In a word, we were overwhelmed by everything that was going on but also determined to overcome the epidemic. The acute stage was followed by adaptation stage, from 26 March to 21 April during which concerns, fears and thoughts about coronavirus, as well as the degree of compliance with protective behaviour stopped growing but stayed at relatively stable level. In other words, that was the stage in which after the initial shock all of us started functioning smoothly and adhered to all recommendations. Finally, during the relaxation stage, from 22 April to 7 May, people started rating their fear, concerns and being preoccupied with coronavirus as lower, which also applied to their preventive behaviour and credibility of information from different sources. This sudden and not particularly wise relaxation started immediately after the longest curfew, which lasted more than 80 hours, during which a significant relaxation of measures was announced to start only 10 hours after the end of the curfew. Such directly opposing messages – being in complete lock down, on one hand, and being completely free, on the other – sends people, psychologically speaking, a message that there are no unambiguous reasons behind the measures. This caused confusion among people, which in combination with the feeling of immense fatigue and pressure caused by the lockdown led to relaxation of self-protective behaviour. Wearing of face masks is not a social imperative, so it is the subject of humorous discourse that started with the “ridiculous virus” – thus, the face masks become ridiculous, as well, and those wearing them sometimes become ridiculed. Important people and decision-makers don’t wear them or wear them sporadically. Therefore, the subject that we discussed in our latest blog, which is that participants in our study clearly understood political and economic, but not the medical reasons for lifting the measures, is no surprise. At the end of the state of emergency we found ourselves exhausted and finally the great fatigue replaced the fear, as we followed the elections and gathered strength to get at least some peace and enjoy in few days of the summer, hoping that the economy is not too severely damaged.

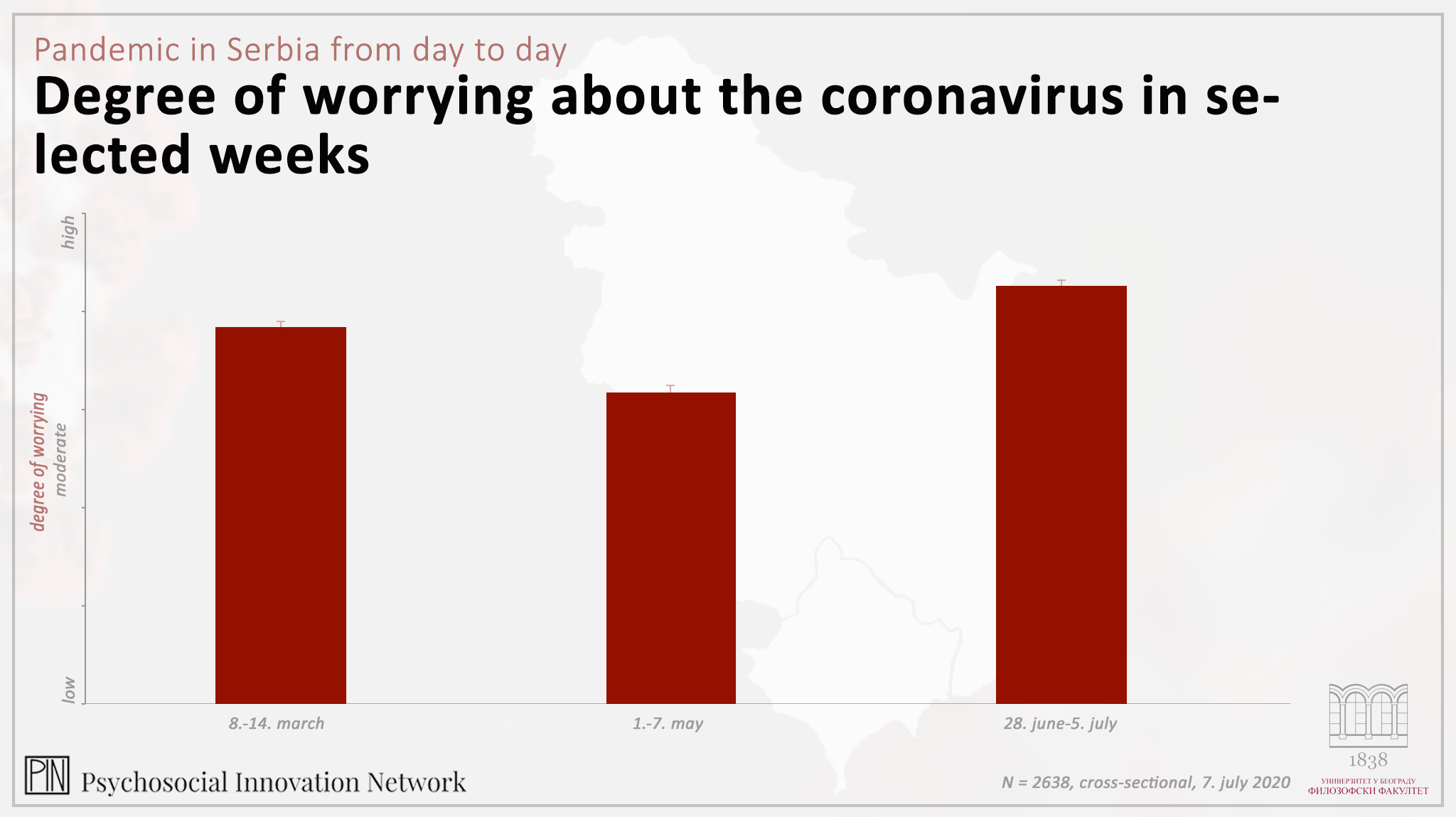

Today, two months after the state of emergency has been lifted, the psychological profile looks the same as it was in the beginning. Our concern is at the same level it was during the first acute stage when the state of emergency and curfew were introduced, when the first death from COVID-19 was registered, when curfew was extended and when we had no idea what was going on. What is different today is that we went through 4 months of psychological stress and fatigue and we are not entering the today’s stage mentally strong and intact, but quite the opposite. We still know very well how we are supposed to behave and we are very responsible in that regard. Being exposed to the most diverse information from various expert and non-expert sources for two plus two months didn’t stop us from being solidary and agreeing about the importance of protecting ourselves and the others, but, unfortunately, it led to complete loss of trust in health institutions and increased our trust in doctors and scientists.

Our daily lives remained subdued to the current epidemiological situation – most of us on the scale from “not at all” to “very much” state that we are very concerned and scared, that we spend a lot of time thinking about coronavirus and consider COVID-19 to be a very severe illness. On the other hand, people are no longer so sure that the infection can be contained, although they report about being committed to preventive behaviour. We continue to wash our hands frequently, choose not to attend events with large groups of people (we cancel our trips, buy and use protective medical equipment (face masks, alcohol, etc.), we spend more time at home, we avoid close contact with other people. As before, out of all recommended preventive measures the request to not touch our face remains the hardest one and you can find out more about the reasons for that in our previous blog. We are also sure that in case we got sick we would absolutely take care about our personal hygiene and hygiene of our home, we would self-isolate, avoid family members and would not go to work. Considering that today 7 out of 10 people know someone who contracted the coronavirus, that healthcare system capacities are at their limits, all the heart-breaking news coming from different parts over Serbia, it’s no wonder people averse and reluctant to visit their health clinic before checking the procedure over the phone.

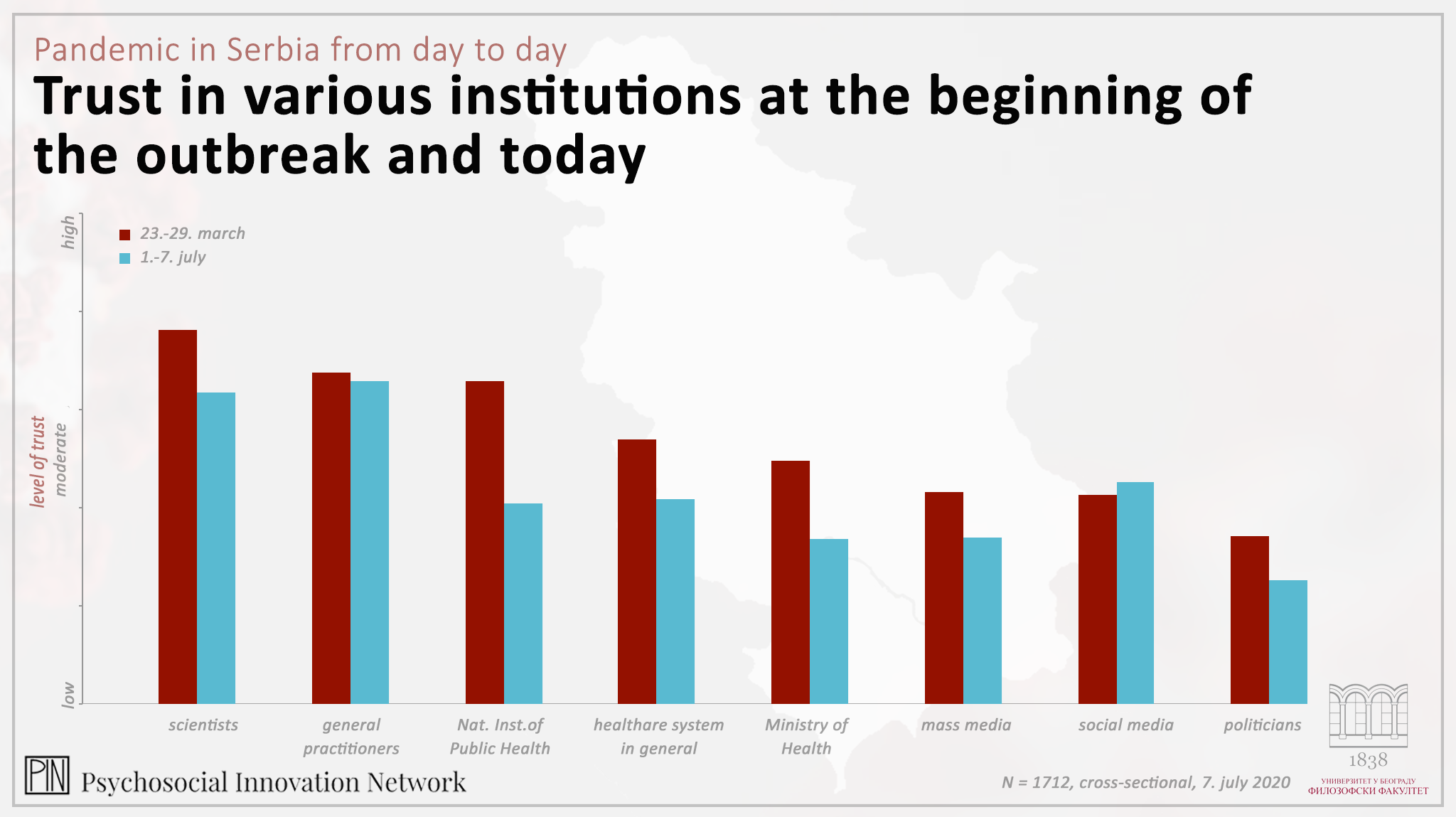

Figure 1. Trust in various institutions at the beginning of the outbreak and today

Figure 1. Trust in various institutions at the beginning of the outbreak and today

Our trust in different information sources is at moderate level – not too high and not too low. We trust personal doctors and scientists as sources of information and by far the least we trust the politicians – no one believes them on average and that is something that hasn’t changed over these 4 months. Somewhere in-between, but closer to the politicians is our trust in traditional media, which we trust the same as the ministry of health, while we have slightly higher trust in Batut Institute and the healthcare system as a whole. We trust social media more than the public healthcare institutions. Correspondingly, our assessment of the credibility of information on coronavirus depends on the source of such information. Once again, information from the scientists are the rated as the most reliable, followed by information from doctors appearing on various shows, representatives of the Serbian Medical Chamber, Batut Institute, journalists, while information from the representatives of the ministry of health are considered the least reliable. Trust in different sources information decreased. If we were to rank the trust for weeks from March 23 to 29 and for today, we would see that, although the highest trust is still put in scientists and personal doctors, Batut Institute, which was the healthcare institution that was the trusted the most, fell to the fifth place and today we trust representatives of Batut Institute less than we trust social media which find themselves in the third place. Similarly, representatives of the Ministry of Health dropped from the fifth to the seventh place, which they share with traditional media (television, radio, newspaper).

Finally, based on our data, overview of the psychological state today, after the first four months of the epidemic in Serbia, shows that we are mentally exhausted, scared by the disease the same as we were at the beginning and that we lost trust in institutions we used to trust the most in the beginning, such as Batut Institute.

However, what we learned was that we were capable of understanding the severity of the infection on our own and of doing everything we could to prevent it and stop its spread. It is one of the most important lessons, although it came at high price.