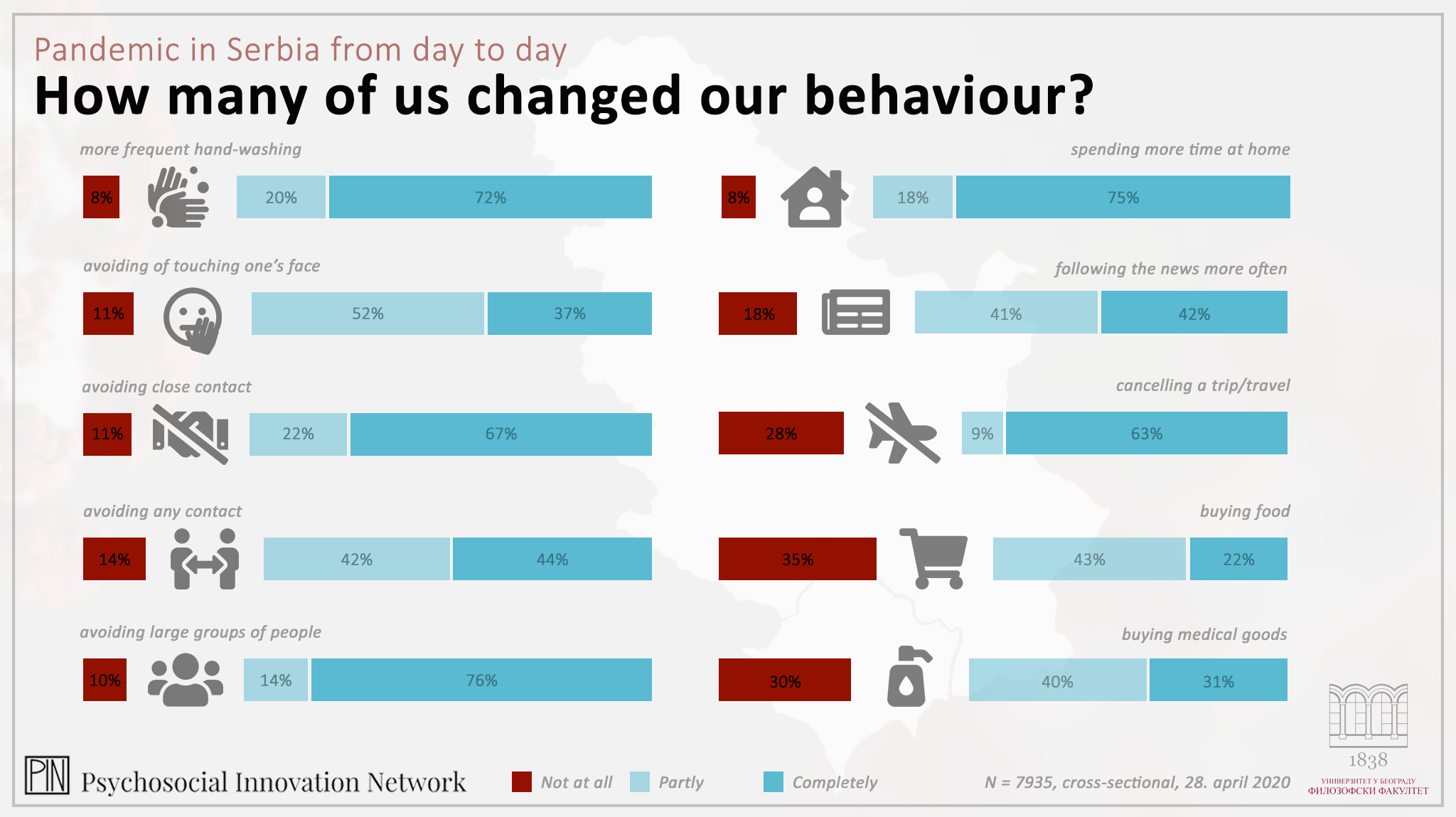

The stopping of the epidemic depends on many factors, but every aspect of the strategy against coronavirus is based on reducing the physical contact between people in order to prevent or slow down transmission of the virus. Reduced contact, regardless whether it is the result of an order, someone begging for it, a public plea or imposed measures, requires the people to change their behaviour. In order to be efficient, such behavioural change must be fundamental and be implemented as soon as possible, because the first weeks are critical. Although it doesn’t seem so at first, it is a huge thing to ask. Let’s remember how hard it is to change our behaviour, even when we know how harmful it is. Take smoking for example. It is even harder to change our behaviour when we don’t fully understand why are we expected to do so. One of the reasons for which we are expected to change our behaviour was and still is solidarity. The experts, therefore, asked us to be disciplined for the sake of solidarity. Vast majority of us actually complied to that request – we were nice, disciplined and showed solidarity: we stayed at home, washed our hands, avoided public gatherings and close contacts with other people, cancelled our trips. Besides that, we made an effort, a more or less successful, not to touch our faces. Why are we so much better at developing a habit of washing hands and keeping social distance than we are at learning to avoid touching our face? Face touching is an unconscious habit, and as such it is a very challenging one to lose, even temporarily.

Response Speed

The “behaviour of a common man” and our compliance with the imposed behavioural measures are the key factors in stopping the epidemic or pandemic, as it is explained in many scientific articles on the issue of society’s response to epidemic in various countries (e.g. Ebola, SARS, bird’s flu). Epidemic is an epidemiological challenge, as well as a social one – if not for anything else, then for existing only in the human society. Therefore, if a healthcare system of a society, any society, is not capable of “fully absorbing” the epidemic, the individuals, i.e. citizens are actually the ones expected to carry the burden of protecting the public health. Previous experiences show a social response based just on biomedical approach and healthcare instructions for the people is just not enough. Moreover, in order for epidemiological instructions to be successful, the authorities, from expert team to local self-governments, and the media are required to apply a communication strategy in which they support each other, while being a bridge between the experts and regular citizens. If there is no communication with the people and if they are not educated on what and why they are required to do at the same time as they are being asked to be disciplined and being subjected to restrictive measures, than such discipline will take more time to achieve and it will be short-lived. When citizens are (justifiably) required to isolate or self-isolate a paradox of resistance and lack of trust regarding the measures starts appearing. Such reaction is the result of the gap between the request to “(self)isolate” and expectation that modern science and healthcare system should be able to treat and treat the disease and prevent its spread. Such psychological reaction, which is already described in the literature and therefore expected, causes some valuable time to be lost during the first weeks in the race against the spreading contagion. It is therefore of critical importance to timely, comprehensively and in a calming way notify and explain the measures to the people and provide them with wide psychosocial support. In short, people need time to adopt a new behaviour. Even in much simpler situation, for example, when we get a new job, it takes almost a month to learn all the new rules of conduct. During the pandemic, that kind of time was a luxury we didn’t have.

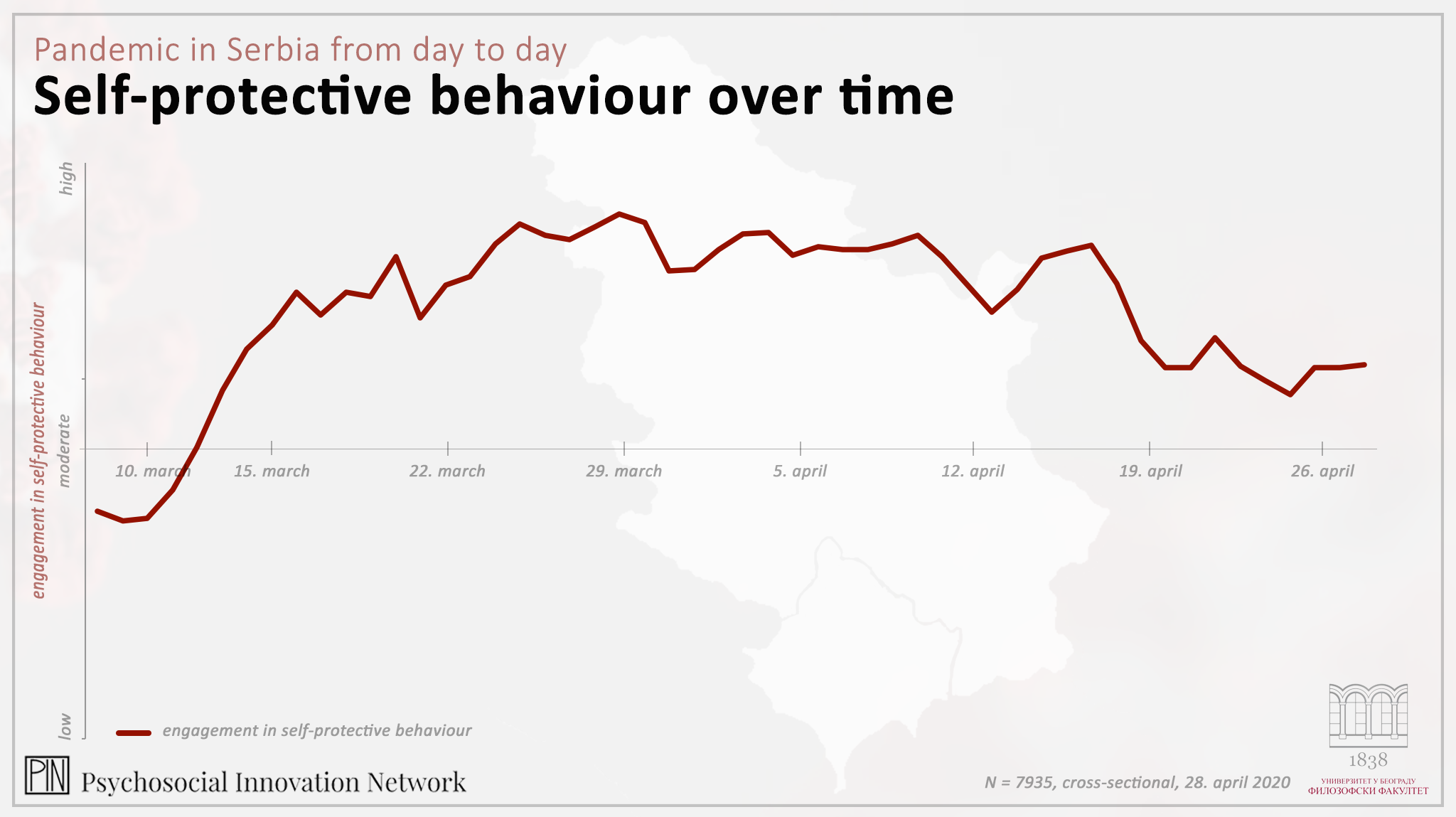

How Much Time It Took for Us to Become Disciplined?

We were able to quickly achieve high level of expected self-protective behaviour. As early as on 15 March we were highly engaged in self-protective behaviour and such level was diligently maintained during this entire period, even when we were being scared by messages that threatened us with overfilled cemeteries. Significant decline in compliance with measures or relaxation was observed on 19 April. Even with this decline, self-protective behaviour is much more present now than it was at the very beginning of pandemic.

Why Did We Relax at That Point?

The longest curfew, which meant 84 consecutive hours of lockdown, started on 17 April, which was the date when self-protective behaviour started to decline and got to the lowest point on 19 April. This is no surprise. People spent four days locked in their houses and it seemed to them they have nothing to protect themselves from. Regardless of the stress caused by staying inside and organizational challenges they had to face, people felt protected from the virus because they were not on the streets. In psychological terms the four-day curfew was very dynamic. On the second day, in the midst of the lockdown, on the night of 18 April, President Vučić announced that measures will be eased immediately after the curfew, starting from 21 April. Just as a reminder, easing meant shorter curfew, opening of craft shops, lifting suspension on construction works. It was also announced that people older than 65 would be allowed to leave their homes, which was not only strictly prohibited up to that point, but served both as motivation and sometimes as a threat and a reason for us all to stay home. Such official statements, announcement and decisions on easing of measures, which came during the longest lockdown until then, caused people to relax, because the message – “the end is in sight” – was in striking contrast with the lockdown and seen by exhausted citizens as a signal to relax, something we are no strangers to. Concerns about getting infected naturally decreased as we were closing to the end and we thought “if I haven’t caught it by now, now there is even less chance that I would catch it”. It was around that 21 April, when the society started to slightly open, when pensioners started leaving their homes and when all measures were eased, that we observed a small increase in self-protection, but it lasted only for one day. Today, although we are trained on how to cope with the new situation and we have learned how to behave properly, we are exhausted by two months of continuous anxiety and uncertainty. However, it seems that self-protective behaviour became a habit to a certain degree and it remains to be seen how long it will last. A small share of participants in our study, who stated they did not comply with all the recommended measures, explained that they did not wear gloves and masks because they were not available and they considered some measures exaggerated and illogical. There was also more than a few who said that “they complied with the curfew, although they considered it to be completely meaningless”.

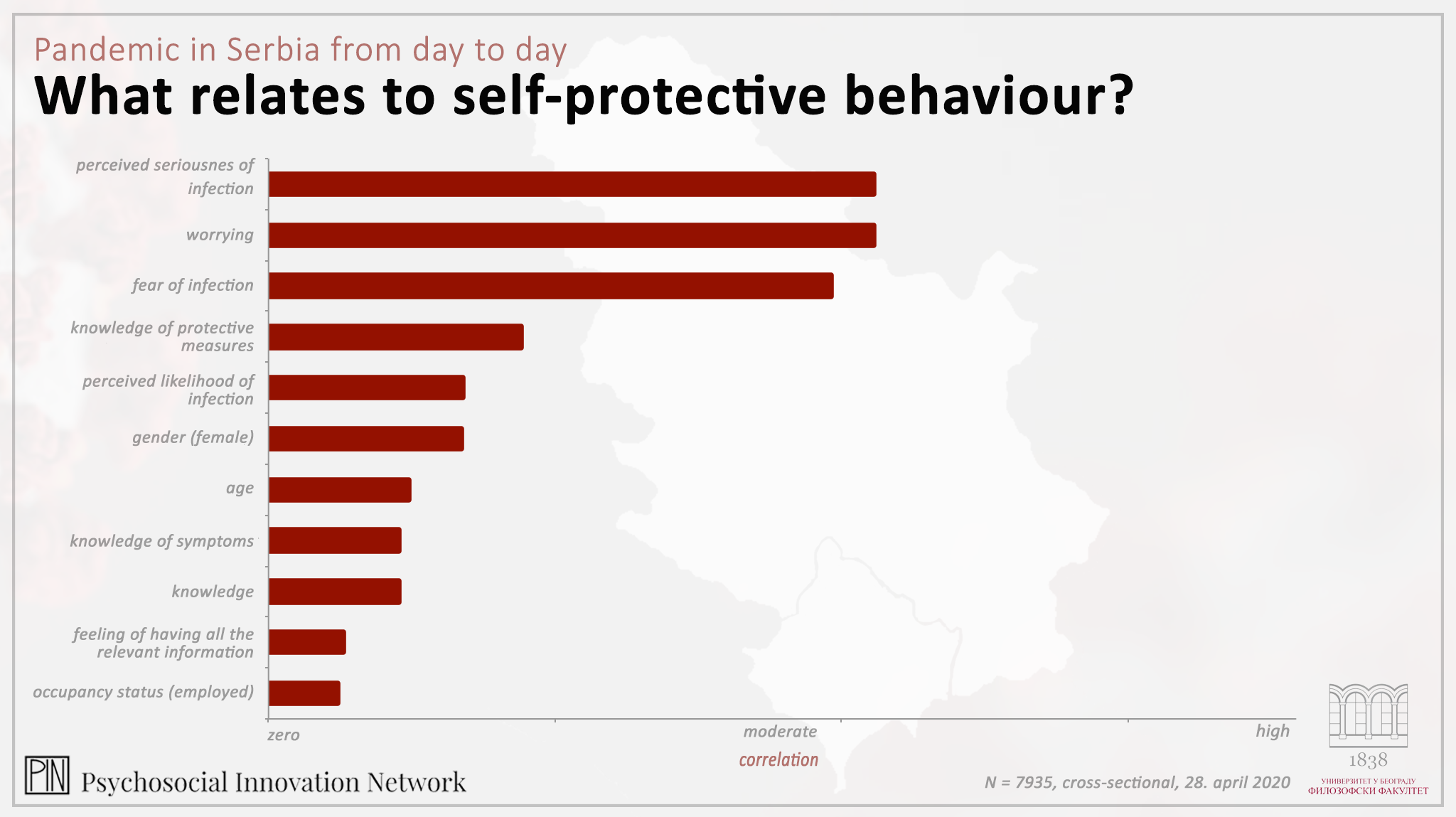

Finally, the disciplined behaviour during pandemic does not take place in vacuum. Not everything in our lives was just fine and the pandemic did not “just” require us to change our behaviour. It was a necessary thing to do, but had to do be done while organizing work, our family life, caring for our household members and our pets, buying groceries, worrying, being scared, facing uncertainty and losing the feeling of being in control. Being able to achieve a functioning balance in all that, both mental and behavioural, was a huge challenge. Real concerns and realization that this infection and situation caused by it are serious, and not some most ridiculous infection ever, came with the disciplined behaviour. Those who were more worried and afraid, thus being capable of understanding the seriousness of the situation, were the ones who protected themselves the most. It is interesting that those who underestimated the seriousness of the situation in the early phases of the epidemic, today became those who protect themselves more, which might be an illustration of the psychological defence mechanism known as overcompensation. The self-protective behaviour is, to significantly lesser extent, related with the awareness of precautionary measures and even less with the knowledge. Therefore, knowing how to protect ourselves is not that important, since it is something everyone learned by now. It is much more important if we consider a behaviour to be meaningful – if we are scared of getting infected and if we think the infection is a serious matter, than we think of the self-protective behaviour as more purposeful, than it is seen by someone who is less afraid of the current situation. Being aware of the precautionary measures does not mean we will comply with them and not everyone is equally scared of the infection, so some people protect themselves more, some protect themselves less. Giving timely and clear explanations regarding the purpose and meaning of the self-protective behaviour serves to avoid the fear becoming the only driver of our behaviour, which although it is called self-protective is actually there to protect us all.

Finally, the disciplined behaviour during pandemic does not take place in vacuum. Not everything in our lives was just fine and the pandemic did not “just” require us to change our behaviour. It was a necessary thing to do, but had to do be done while organizing work, our family life, caring for our household members and our pets, buying groceries, worrying, being scared, facing uncertainty and losing the feeling of being in control. Being able to achieve a functioning balance in all that, both mental and behavioural, was a huge challenge. Real concerns and realization that this infection and situation caused by it are serious, and not some most ridiculous infection ever, came with the disciplined behaviour. Those who were more worried and afraid, thus being capable of understanding the seriousness of the situation, were the ones who protected themselves the most. It is interesting that those who underestimated the seriousness of the situation in the early phases of the epidemic, today became those who protect themselves more, which might be an illustration of the psychological defence mechanism known as overcompensation. The self-protective behaviour is, to significantly lesser extent, related with the awareness of precautionary measures and even less with the knowledge. Therefore, knowing how to protect ourselves is not that important, since it is something everyone learned by now. It is much more important if we consider a behaviour to be meaningful – if we are scared of getting infected and if we think the infection is a serious matter, than we think of the self-protective behaviour as more purposeful, than it is seen by someone who is less afraid of the current situation. Being aware of the precautionary measures does not mean we will comply with them and not everyone is equally scared of the infection, so some people protect themselves more, some protect themselves less. Giving timely and clear explanations regarding the purpose and meaning of the self-protective behaviour serves to avoid the fear becoming the only driver of our behaviour, which although it is called self-protective is actually there to protect us all.

FOR THOSE WHO WANT TO KNOW MORE

In psychological studies we very rarely research just one aspect of the psyche or behaviour. We are usually interested in interconnections between the observed phenomena, for example, emotions and self-protective behaviour. During this study, considering the subject of today’s article is compliance with measures and switching to “pandemic mode”, we carried out an analysis to find out which mental path leads us to behave in accordance with prescribed measures. The path starts with a doctor and looks like this. In our study we observed very high trust in scientists, doctors and medicine, which will be covered in more detail in future articles. These are exactly the sources we trust the most regarding the coronavirus epidemic. When these sources announce that the situation is serious, we then become really concerned and afraid. In order to calm down and establish subjective control over the situation, we inform ourselves, trying to understand the situation and comprehend what’s going on. In the end, that is what drives us to comply with the measures. This path would be different if a doctor, healthcare worker or a scientist would say that situation is not that serious, which already happened at the very beginning of the state of emergency. Luckily, we did not fall for that.