Until two months ago we did not pay much attention to coronavirus. When we heard about the first case of this disease, we had only a few days to get scared, then calm down, buy everything we needed, but being careful to leave enough for the others, learn how to behave and how to care for the loved ones, without putting them into danger. Along the way, without even wanting to do so, we learned many things about the novelty coronavirus, as we used to call it – from difference between the COVID-19 disease and the name of the virus SARS-Cov-2, to incubation period of the disease. Along the way we had to learn how to properly put on a mask, does a mask provide protection and to whom, how does a virus replicate itself and where, how is it transmitted, how long it can survive, under what circumstances and on which surfaces, what are geometric and arithmetic growth, what does it mean to flatten the curve and why is it an imperative for all the healthcare systems, and not just for our healthcare system, flawed as it is.

Vast psychological knowledge shows that knowing and understanding a phenomenon or an issue, such as, for example, pandemic or the lifecycle of a virus, how it replicates and harms us, is an important protective factor. The knowledge protects us from false information, frauds and abuse, but most importantly allows us to understand the importance of behaving in the way we are asked to. If we understand why it is important to behave in a certain manner, not only the protective measures will be easier to implement, but we will be ready to comply with them in a timely and willing fashion, over an extended period of time. Being able to understand calms us down and the meaning makes it easier to bear the hard aspects of isolation and self-isolation. This is why in this article we will discuss how much we think we know and how much we actually know about coronavirus, where do we get information from and how frequently, compared to the time “before coronavirus”, how do you estimate your chances of getting infected and how all these questions are connected to each other.

Sources?

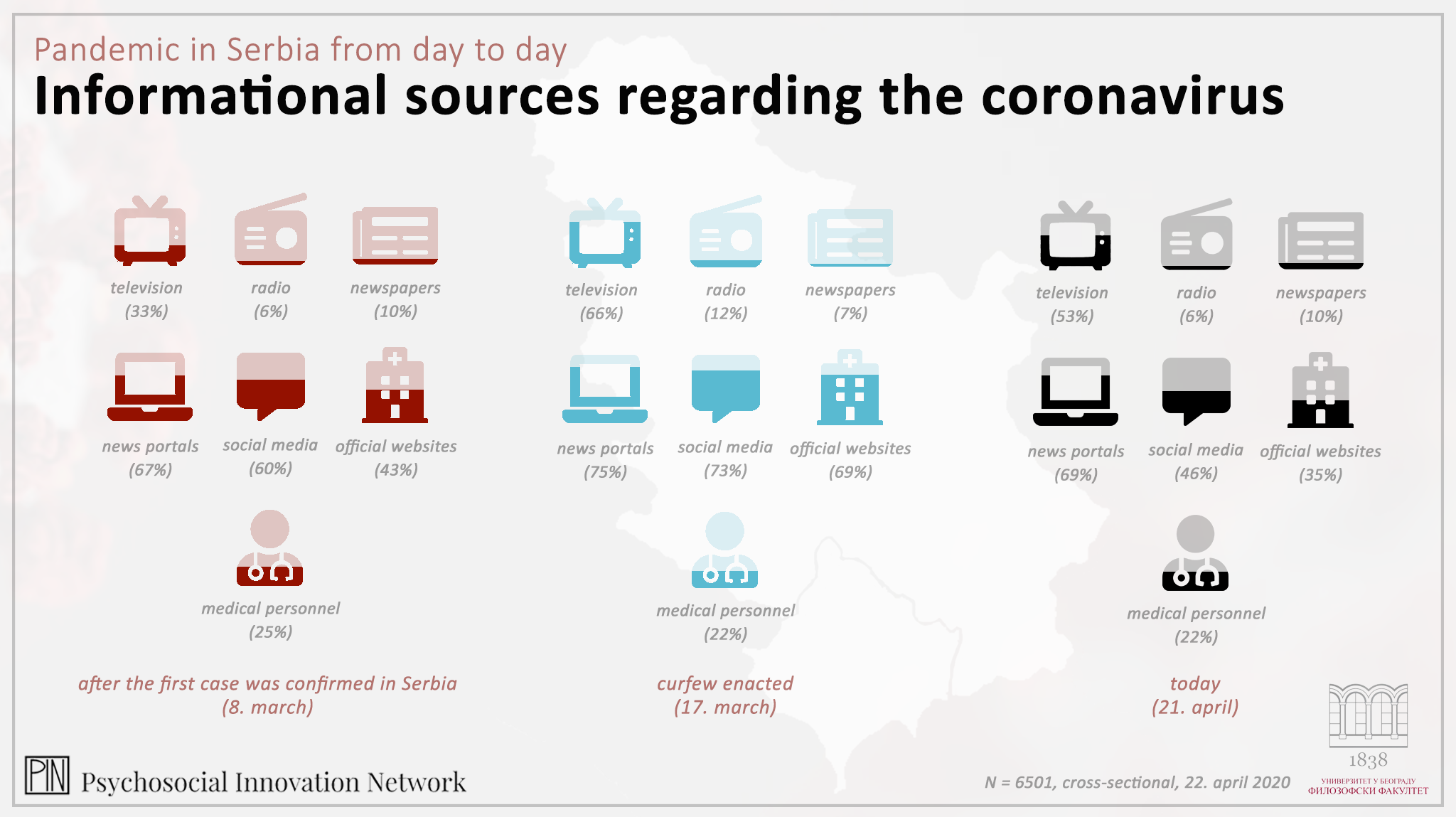

Over the last couple of months, TV, news portals, social networks and websites of official institutions, such as Batut Institute, were the main sources of information for most of us regardint the infection and spread of coronavirus.

On the other hand, a relatively small number of us gets information from the radio, newspaper and from healthcare professionals directly. If we examine the period starting with the first confirmed case of coronavirus and ending with the week during which state of emergency was declared, curfew was imposed and epidemic was declared, there has been an increase in information obtained from television, radio, social network and official websites of institutions followed by slow, but steady decline until today. The only exception from the rule is radio, which from 23 March dropped to the same level on which it was before the reported increase. The reason probably lies in the fact that most people listen to radio in their cars, and since we leave our homes only to go to a grocery store or to take a walk, we don’t go to work and therefore drive less, there are less opportunities to use this media. As for the newspaper, from the beginning of the study only a small number of participants stated they read the newspapers. Reasons for this are that we usually get information from other sources, such as television, and that newspaper is a slower communication media, as well as the fact that we mostly stay at home, making the newspaper less available, the issue we already discussed in the article about information (https://psychosocialinnovation.net/2020/04/18/strah-vesti-i-briga-iz-dana-u-dan/). Very few of us get information from healthcare professional, probably because most of us do not have acquittances and friends working in the healthcare system. Still, the number of people getting information in that way was steady and did not change from the beginning of March, speaking to the fact that reliability of these sources did not change.

How Much We Really Know and How Much We Think We Know?

We asked you 17 questions about coronavirus. The correct answers to some of the questions changed depending on the information available at the time, i.e. reported by the media and thus available to everyone. Some of the questions were easier (how is the virus transmitted), while, for example, information on safe distance from an infected person varied from half a meter to 3-4 meters depending on various media. The same was with the explanations about the necessity of wearing a mask and when a mask should be worn. In case of some questions, it wasn’t even possible to give a correct answer, because it still unknown even to the professionals (e.g. how long a virus can last on hard surfaces).

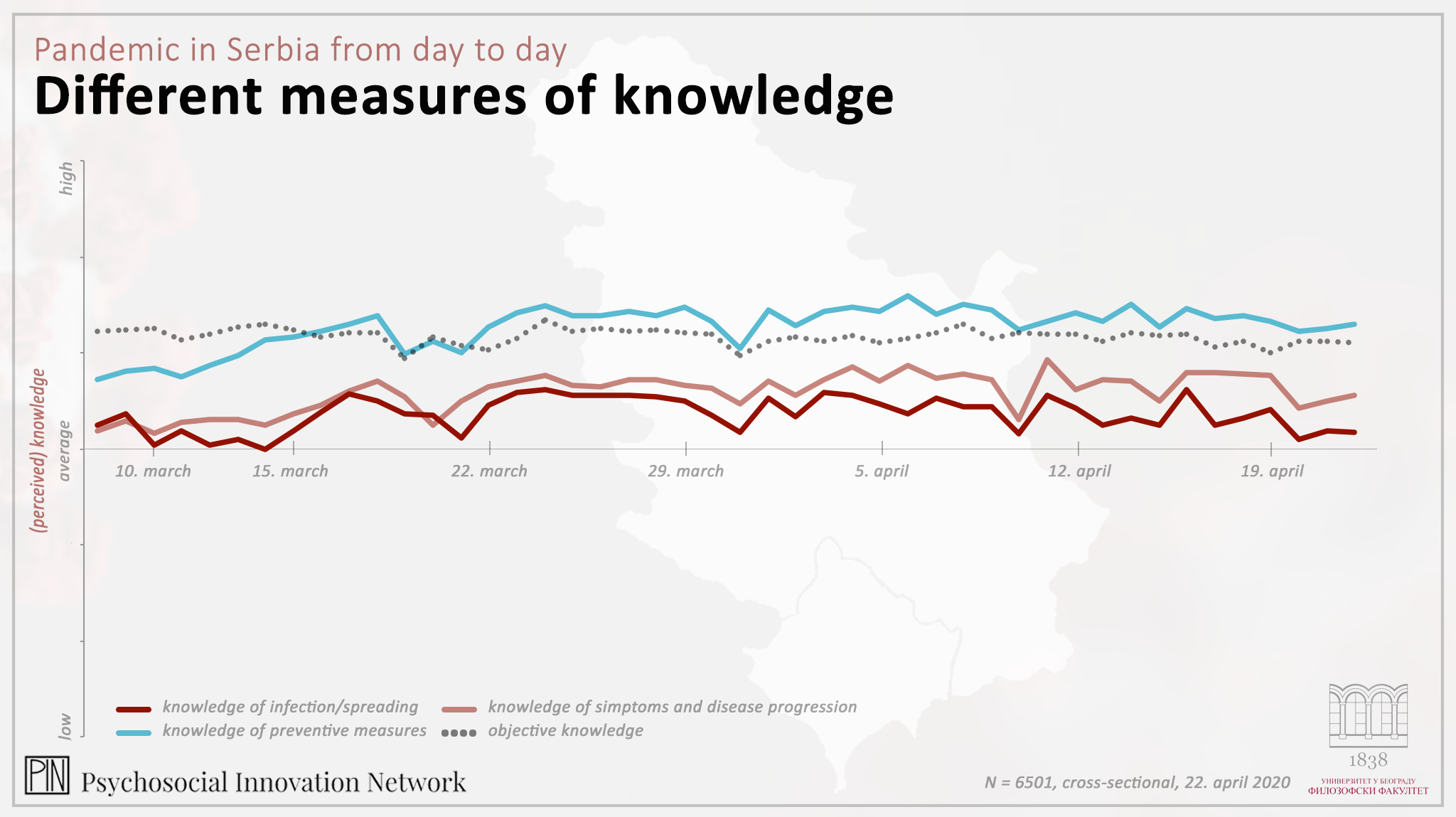

Our general knowledge of confirmed facts about coronavirus was at a very high level – most of us responded correctly to 80-90% of the questions. This objective knowledge has very quickly grown from the beginning of pandemic and the acquired level of knowledge remained the same over the following period. This is why the objective knowledge is shown on the graph as an average value over the entire period (dashed line). The most confusing questions were about could the transmission rate of COVID-19 be compared to transmission rate of seasonal flu and what is zoonosis. On the other hand, the questions with the most correct answers were how coronavirus is transmitted, who has the higher risk of contracting sever form of the disease and are antibiotics effective for treatment of the disease.

We also asked you to estimate how confident you are in your knowledge about coronavirus. Answers to these questions show that we are not so confident that we have all the necessary information about the infection and spread of coronavirus, although we became much more confident about our knowledge with the declaration of the state of emergency. On the other hand, over the time we grew increasingly convinced that we knew the symptoms and the course of coronavirus infection, which also applied to precautionary measures against the spread of coronavirus.

Finally, it should be noted that persons that performed better on our test, presumably the ones that really have more information and actual knowledge on the virus, are the people that more frequently use the media and healthcare professionals as their source of information. On the other hand, those who (wrongly) believed they knew more than they actually did, e.g. those whose subjective estimate was that they had better knowledge and disposed with all the necessary information on infection, spread, symptoms and the course of disease, while giving wrong answers on the test, also got more information directly from healthcare professionals, but less frequently used different types of media. Therefore, getting information from the sources we consider reliable contributes to our subjective impression that we dispose with all the important information.

Finally, it should be noted that persons that performed better on our test, presumably the ones that really have more information and actual knowledge on the virus, are the people that more frequently use the media and healthcare professionals as their source of information. On the other hand, those who (wrongly) believed they knew more than they actually did, e.g. those whose subjective estimate was that they had better knowledge and disposed with all the necessary information on infection, spread, symptoms and the course of disease, while giving wrong answers on the test, also got more information directly from healthcare professionals, but less frequently used different types of media. Therefore, getting information from the sources we consider reliable contributes to our subjective impression that we dispose with all the important information.

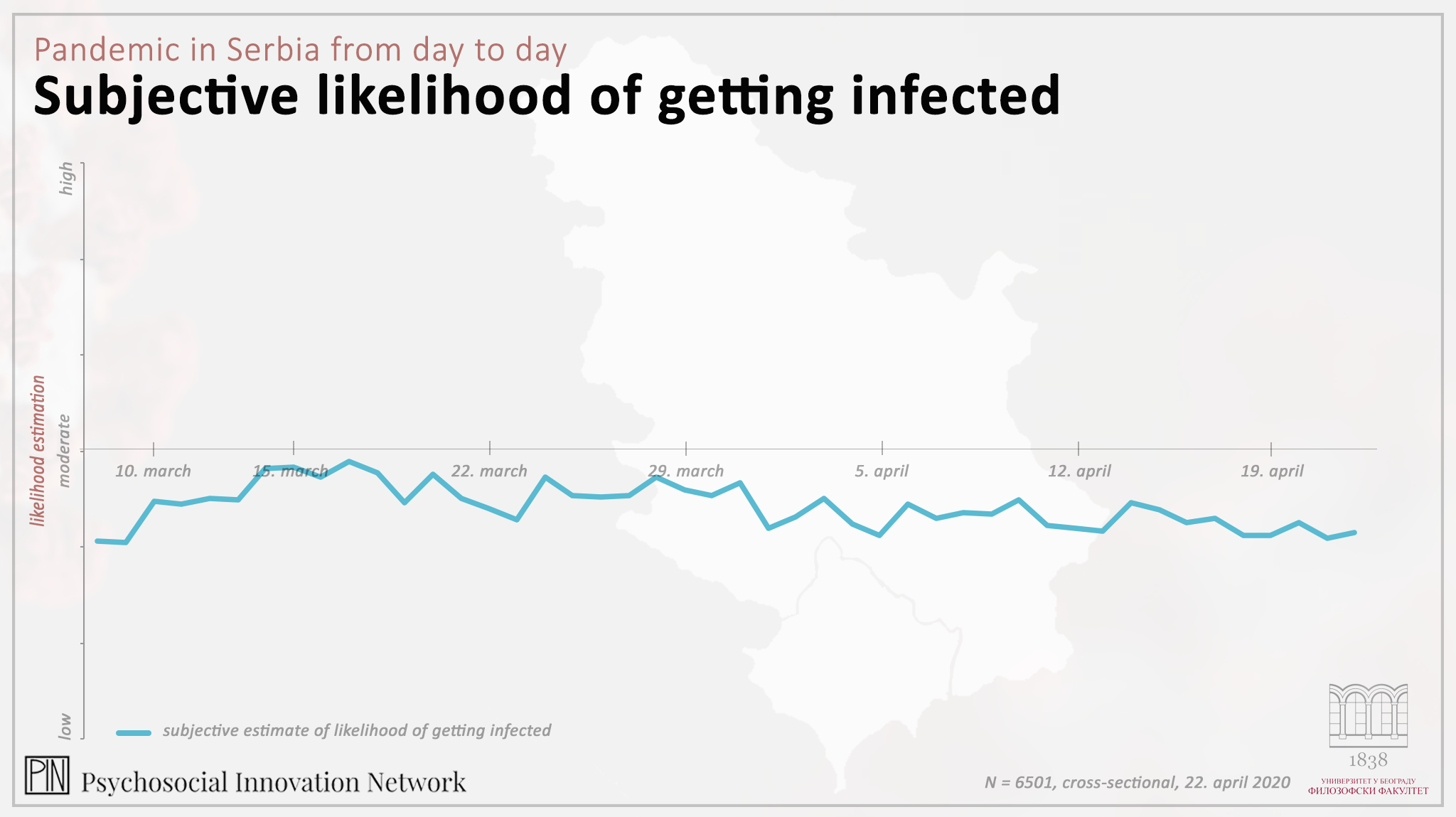

The level of objective knowledge and the level of confidence in our knowledge are also related to our estimate of the chance of getting infected by coronavirus – the more we believe we have all the important information on coronavirus, the less it seems probable to us that we will get infected. On the other hand, the more objective our knowledge on coronavirus, i.e. on spread, symptoms, risks and proper protective measures, the higher is our estimate that we can get infected. This leads us to a conclusion that a high subjective estimate of our knowledge on coronavirus has a function of calming us down. On the other hand, objective, actual knowledge on the matter has the opposite effect – causes the reality to be observed objectively and accordingly leads to correct assessment of risks.

Finally, the people with the least number of correct answers, besides less using the media as the source of information, also overestimate their knowledge – they think they know more than they actually do. This represents a significant challenge in development of public policies and communication strategies, because it seems that in this type of situation people quickly develop a feeling of “knowing everything they need”, despite their decision not to get informed or not being able to get to correct information. This is particularly important considering the complexity of information environment we live in and in which we are constantly bombed by false information, unverified and quasi-medical stories and advices.

Finally, the people with the least number of correct answers, besides less using the media as the source of information, also overestimate their knowledge – they think they know more than they actually do. This represents a significant challenge in development of public policies and communication strategies, because it seems that in this type of situation people quickly develop a feeling of “knowing everything they need”, despite their decision not to get informed or not being able to get to correct information. This is particularly important considering the complexity of information environment we live in and in which we are constantly bombed by false information, unverified and quasi-medical stories and advices.

How Much Did We Follow the News Before the Pandemic and How Much We Follow the News Today, During the Pandemic?

For most of us, we learned everything we know today about coronavirus from the media, from the news or from the Internet. We learned a part form the news, while we researched the rest on our own. In both cases, most of were never given a manual, we didn’t have training on important information and how to act, so we relied on the news more than we had before. That’s why we wanted to know did you follow the news before the “coronavirus situation”, before the first case was detected in our country and after that (dooms)day. At the very beginning of March, while the memories of the previous year still lingered in our minds and before our lives were turned upside down, and our freedom, honesty and health started depending on closely following the news, we had the impression that we had previously, but in these days also, followed the news moderately to daily, in other words, just enough to stay informed. However, as the time passed by, more intensive following of the news became the part of our daily lives and we got used to following the news more frequently than before. The memories of the habits we had before the pandemic changed, so it now seemed to us that we followed the news moderately – or, the same as we did the last year.

FOR THOSE WHO WANT TO KNOW MORE

FOR THOSE WHO WANT TO KNOW MORE

We grew accustomed to the new reality and started relying on availability heuristic (availability heuristic) when assessing our former habits, which is one of the many reasoning mechanisms we rely on, particularly when we think about complex situations. Due to availability heuristics we make our estimates on how often we have followed the news during the last year, based not on the last year experiences, but rather on our current experiences. It is easier to remember how often we followed the news recently and then compare that to the last year, instead of trying to remember how much we actually followed the news last year.